A constellation of stars decorate the sky and are reflected in the wings of a loon that floats by on midnight waters. Nearby, a red squirrel is poised and alert, ready to leap from the trunk of a red pine. Like the loon, it’s body is bright, so much so that it’s auburn tail almost appears to erupt in flames.

Animal relatives and midnight skies feature prominently in the artwork of Sam Zimmerman (@cranesuperior on Instagram or Facebook), an Ojibwe artist who is based in Duluth. His art tells stories from Lake Superior and the North Shore and is featured regularly in newsletters distributed by the Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), one of many Indigenous-led organizations in our region that are working to care for nature and re-connect people with the land.

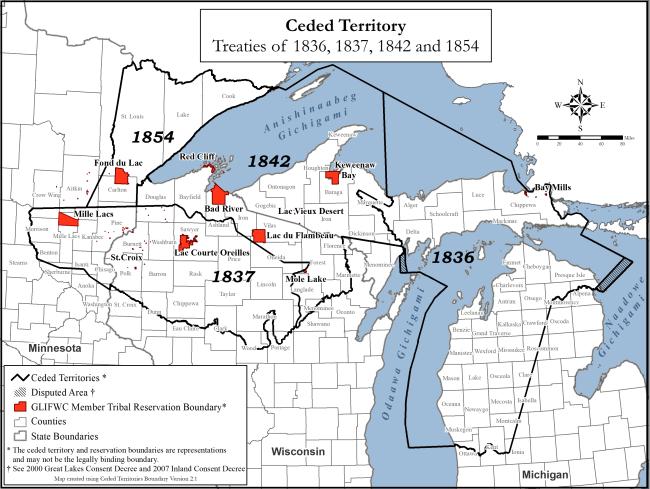

GLIFWC represents eleven Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Michigan, plays a major role in natural resources management, and works to preserve hunting, fishing and gathering rights for Ojibwe people, as established in treaties with the U.S. government in 1836, 1837, 1842, and 1854. Some of GLIFWC’s concerns include protecting the Great Lakes, as well as forests and wildlife in the region, protecting manoomin (wild rice), and responding to climate change and contaminants such as PFAS and mercury (https://glifwc.org).

Closer to the Twin Cities, three Indigenous-led organizations to highlight include Waḳaƞ Ṭípi Awanyankapi (formerly known as Lower Phalen Creek Project), Owámniyomni Okhódayapi (formerly known as Friends of the Falls), and Dream of Wild Health.

Waḳaƞ Ṭípi grew out of community-led efforts to care for and restore the land at Bruce Vento Nature Sanctuary on the east side of St. Paul. The organization offers nature programs and habitat restoration events and is currently constructing a cultural center, which is set to open in 2026. In addition, Waḳaƞ Ṭípi is working with city, state, and watershed partners on a long-term plan to daylight Phalen Creek, which once flowed from Lake Phalen to the Mississippi River but was buried under pavement in the 1900s (www.wakantipi.org).

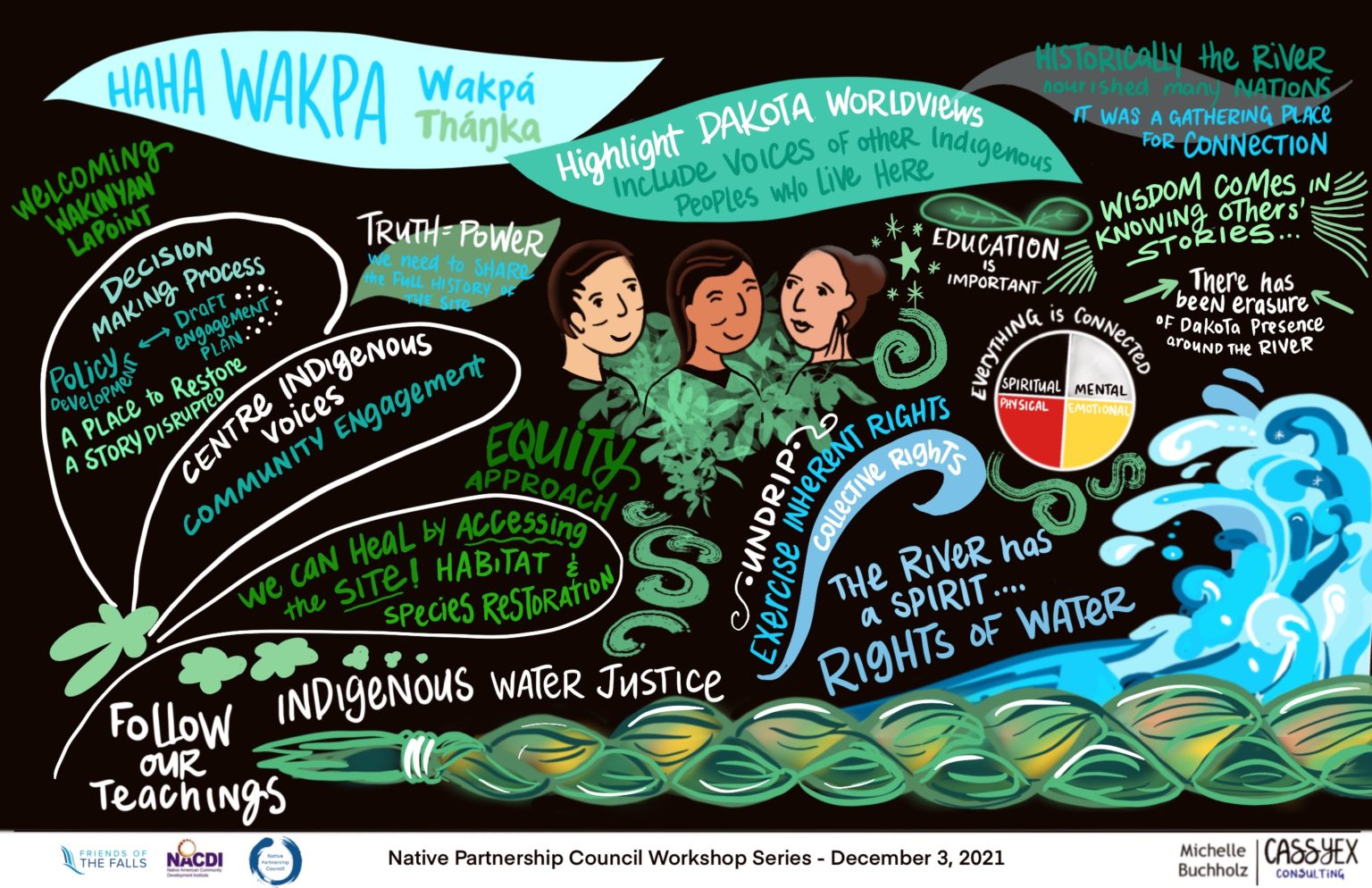

Further upriver in Minneapolis, the Dakota-led non-profit Owámniyomni Okhódayapi has been working to transform five acres of land at St. Anthony Falls into a place of restoration, education, healing and connection. The organization recently received $2.3 million in funding from the MN Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund and says, “Our work is grounded in Indigenous values, like Mitákuye Owas’iƞ (We Are All Relatives) and Mní Wičóni (Water is Life)” (owamniyomni.org).

Dream of Wild Health, is a 30-acre farm in Hugo that works to increase access to fresh, healthy food for Native families in the Twin Cities. The farm also sells produce at farmers’ markets and hosts educational classes for Native and non-Native youth (dreamofwildhealth.org).

One other local organization worth mentioning is Belwin Conservancy, which has been working to protect and restore 1600 acres of prairie, oak savanna, woods, and wetlands surrounding Valley Creek in Afton since 1970. In addition to providing environmental education programming to students at St. Paul and Stillwater Area Public Schools, Belwin has also established numerous relationships with Indigenous artists and organizations in recent years. This includes partnerships with the American Indian Family Center and Anishinabe Academy to provide access to land for education and traditional cultural practices, as well as collaborations with the Imnížaská intertribal drum group, Ikidowin Acting Ensemble (a project of the Indigenous People’s Task Force), and other Native artists to support community events (belwin.org).

Learn more about any of these organizations by visiting their websites, signing-up for a free newsletter, or attending one of many upcoming events.